Department of Sociology

Kenyon College

Treleaven House

105 West Brooklyn Street

Room 202

Gambier, Ohio 43022

USA

Telephone:

Office: (740) 427-5849

Department Office Manager:

(740) 427-5855

Email:

McCarthy@Kenyon.edu

Website Address:

http://personal.kenyon.edu/mccarthy/

EARLY BOOKS

(Click on the jacket cover image for more information about the Table of Contents and Introduction)

MORE RECENT

BOOKS

(Click on the jacket cover image for more information about the Table of Contents and Introduction)

Classical Horizons won the Choice Outstanding Academic Title Award in 2003

LATEST BOOKS

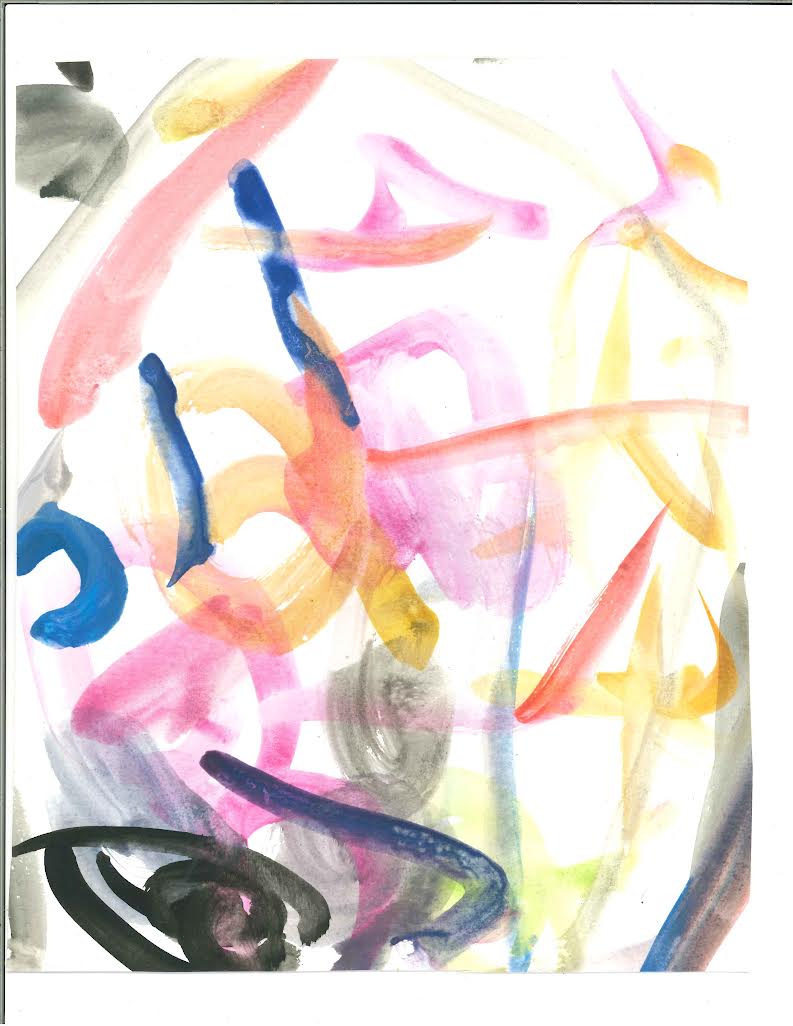

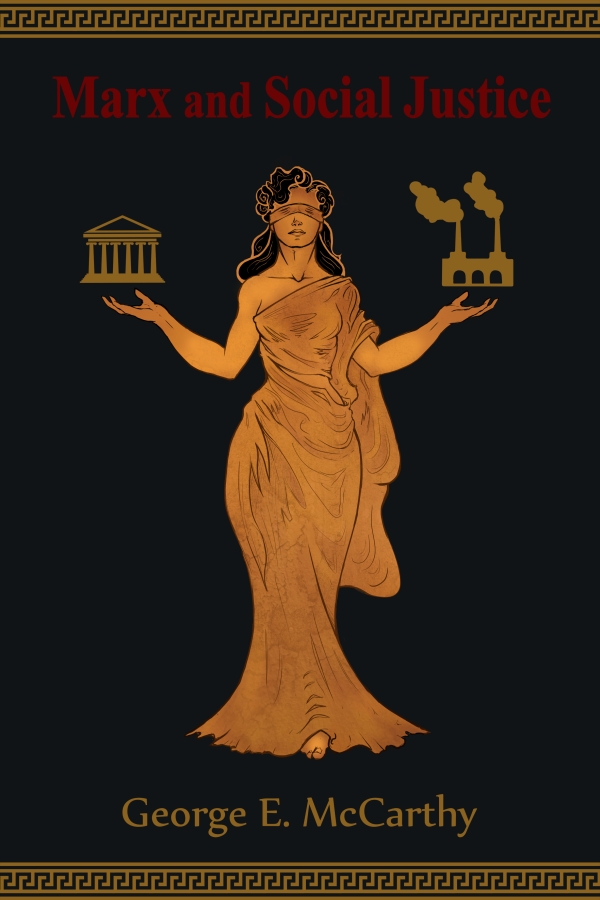

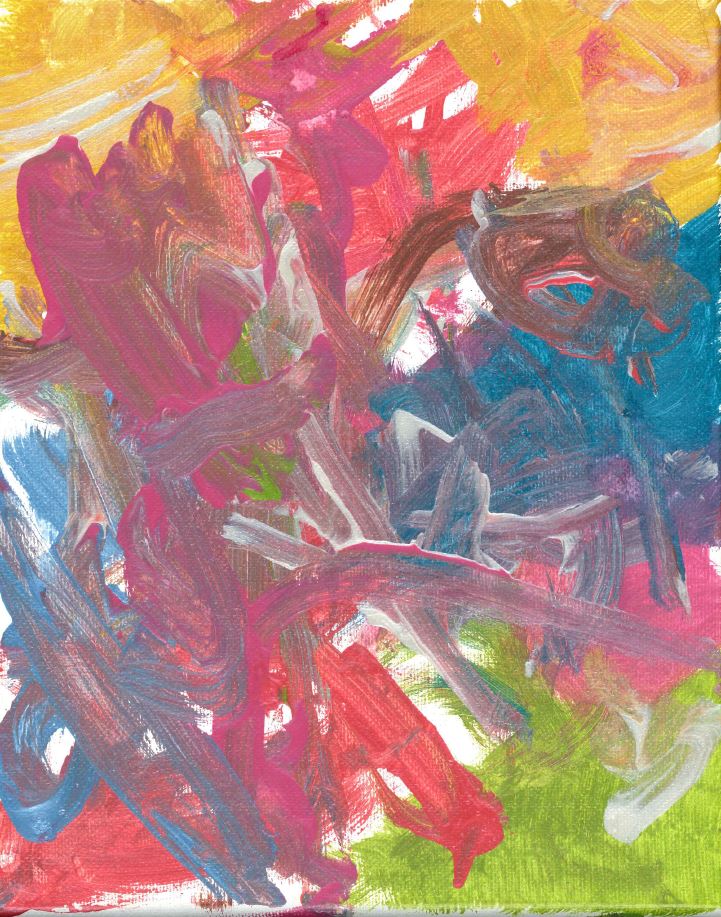

Hardbound Cover 2018

Frontispiece

by Devin S. McCarthy

Greek goddess of Justice

Dike

balancing and integrating the Ancients and the Moderns --

Athenian justice and beauty with modern labor and industry --

as the classical inspiration and imaginative vision of Karl Marx's

Griechensehnsucht

(Longing for Ancient Greece)

and

Horizontverschmelzung

(Fusion of Horizons and Traditions).

with the purpose of creating a classical

vision of workers' associations, economic

democracy, and self-government

"of the people, by the people"

in

The Paris Commune

of 1871

150th anniversary of Marx's Capital (2017) and

200th anniversary of Marx's birth (2018)

NEW PAPERBACK REPRINT EDITION

Paperback Jacket Cover

2019

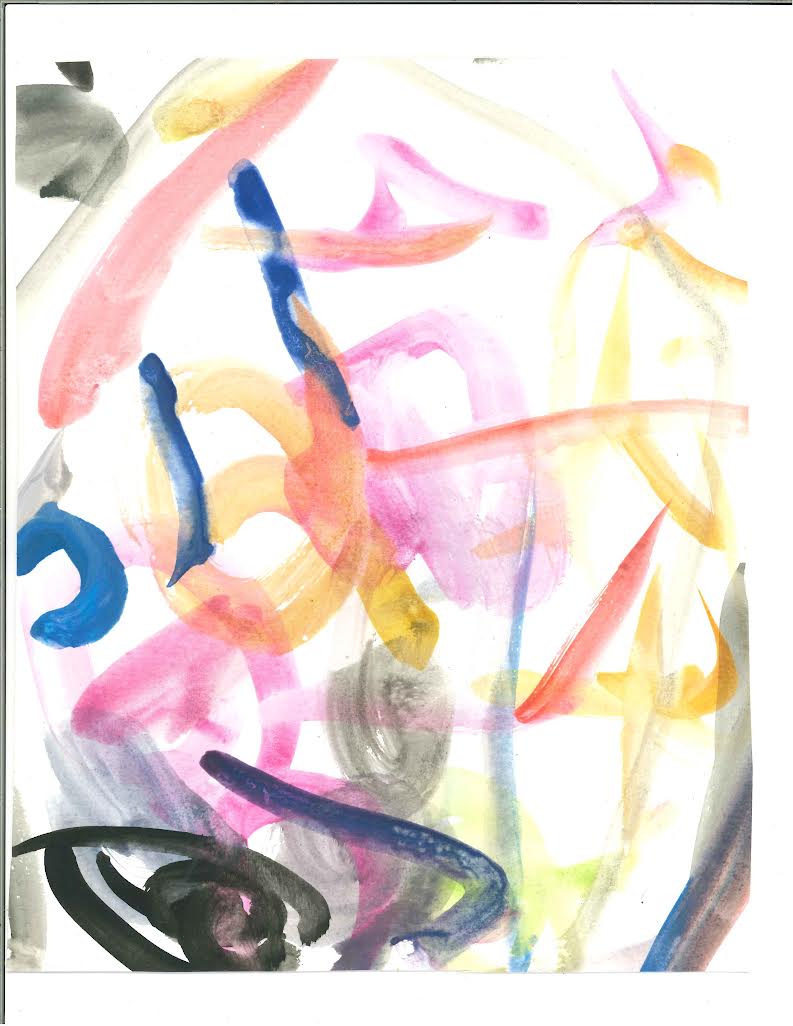

B&W Frontispiece

Haymarket Books

by Devin S. McCarthy

Historical Materialism Series #147

Following closely Aristotle's definition of social justice based on universal and particular justice,

human needs and economic reciprocity, and a critique of the structures and contradictions

of a trade economy (chrematistike), Marx's theories of abstract labor, surplus value,

exchange value, economic crisis theory, overproduction of capital, tendential fall

in the rate of profit, and high unemployment in the Grundrisse and Capital

are an essential part of his modern theory of ethics and social justice.

Marx rewrites and reconfigures Aristotle's Nicomachean Ethics

(morality and virtue) and Politics (political economy and democracy)

into the language of German Idealism of Kant and Hegel, classical

political economy of Smith and Ricardo, and French socialism of

Rousseau, Fourier, Saint-Simon, and Proudhon. Both Aristotle

and Marx argue for the beauty and dignity of a rational and

virtuous life -- moral and intellectual virtue -- within a

democratic polity and moral economy based upon

creative self-determination, human need,

reciprocal fairness, equality, and

the common good.

Social justice refers to the total restructuring of

society and political economy that allows for

the full development of human potentiality,

economic democracy, rights of the citizen,

individual freedom, and human dignity.

This new book on Marx's theory of social justice

attempts to show how he applies and makes

relevant Aristotle's ethics and politics

to an understanding and transformation

of the class institutions and structures

of modern industrial capitalism --

Marx portrays how the heights and

majesty of Ancient Greece provided

Modern Society with its Classical

Humanism -- that is, with

its lost ideals, political

vision, and inspiration

for social justice.

The Enlightenment as the Stairway to the Acheron and Cocytus

Shadows of the Enlightenment examines the dark shadows and political shades of Enlightenment reason which shed light on the hidden assumptions and values underlying Western "science" -- and reveals it as a dark specter haunting society -- from the so-called "Age of Reason" to the present. George McCarthy uncovers the economic, social, and historical origins of modern science, and shows that, deep within the metaphysics, epistemology, methodology, nominalism, and explanatory theories of the natural sciences, lay a priori and innate features which provided the philosophical and political justifications for the technical domination and control of nature and humanity. As we read, we understand that traditional positivist claims to scientific objectivity, realism, and neutrality are in fact embedded with intensely subjective political drives, riven with unarticulated social values and unconscious assumptions. Far from conveying an objective and accurate reflection of nature, the scientific arena fashioned its own concept of "reality," and the field of natural science in particular came to be an ideological mirror of alienation and its social relations of production and exchange.

Breaking with the medieval scholastic tradition, modern science constructed nature as a reified mechanism which could be mathematically measured, empirically predicted, and causally explained and managed. Nature itself was recast as a dead machine suspended in time and space, stripped of any inherent meaning or purpose. The natural sciences were born of a market economy, commercial trade, and industrial production, and were furthermore expressions of the values and institutions of modern capitalism and its class system in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. As such, one of the central roles of Western science has been to provide the formal legitimation for its theoretical imperative to dominate and exploit nature and to reorganize human labor for private profit, property, and power on the basis of rational calculation and technical efficiency.

Examining the importance of the antipositivist traditions within philosophy and sociology, each chapter of Shadows of the Enlightenment highlights a particular school of thought, including the Postanalytic and Postmodern Pragmatism of Quine, Kuhn, Rorty, and Burtt, the Phenomenology of Husserl, Scheler, and Weber, the Existentialism of Schopenhauer and Nietzsche, the Marxism of Sohn-Rethel, C. Wright Mills, Borkenau, Merchant, Leiss, and Balbus, the Critical Rationalism of Albert and Popper, and the Critical Theory of Adorno, Horkheimer, Marcuse, and Habermas. The application of natural science in the process of production leads to scientific management and economic exploitation, while in the academy and social sciences, it leads to the eclipse of reason and the twilight of social theory. Building upon the critical insights of Marx and the debates within the Frankfurt School over the nature of Western science, Shadows of the Enlightenment articulates a new liberatory postmodern science and technology grounded in Aristotle's and Marx's theories of social justice, integrating ancient and modern traditions from classical Greece to the French Revolution and Constitutions of the 1790s, "Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen" of 1789, the Paris Commune of 1871, the Gotha Program of 1875, and the Native American Iroquois Confederacy. Shadows of the Enlightenment invites us to move beyond the falsely mechanical, mathematical, and deterministic view of reality imposed upon the entire planet since the Enlightenment, and to break free from the sense of alienation that binds us all in order to dream of a better and more perfect political and economic democracy of the people, by the people. Marx's theory of social justice moves beyond the abstract and philosophical debates over the nature of modern science and technology in Marcuse's theory of one-dimensional man and his aesthetic rejection of capitalism and Habermas's theory of public discourse and democratic consensus. Following the outline, arguments, and logic in Aristotle's ethics, politics, and sociology, Marx provides the missing concrete historical, political, and economic foundations for both the critical theory of the Frankfurt School and for the political economy and economic democracy of modern social ethics.

Regarding the impact of the Shadows of Enlightenment science, technology, & positivism on the Environment, Workplace, and the Academy --

"For the master's tools will never dismantle the master's house....they will never enable us to bring about genuine change," Audre Lorde, 1984. The rise of Capitalism, Liberalism, and the Enlightenment helped produce the social and structural pathologies of Alienation of the mode of production, human sensibility, and reason (Marx), Anomic Derangement and the loss of collective consciousness (Durkheim), Decadence and Disenchantment of substantive reason in the last man of the iron cage (Nietzsche and Weber), and continues today with the Repression of the unconscious Acheron (Freud) and the Eclipse of Objective Reason and European social theory (Horkheimer). The loss of reason occurred, and continues to occur, because the classical social theorists held views of science that did not conform to the epistemology and methodology of positivism and modern natural science. In the process, the political and ideological shades of Enlightenment reason covered and suppressed the "classical horizons" of the ancient and modern traditions of knowledge, as well as the non-positivist views of science in classical sociology, including Marx's immanent, dialectical, and ethical science, Weber's historical, comparative, hermeneutical, and structural science, Durkheim's neo-Kantian pragmatism, scientific rationalism, and theory of cultural representations, and Freud's depth-hermeneutics, psychoanalysis, and discursive reason.

And with these changes and denials of alternative views of science and knowledge came the loss of critical concepts, ideas, and theories -- Silence. This is the "deafening silence of the primeval forest" and rediscovery of Dante's Inferno for the modern world as we walk down into the darkening and blinding void of existential absurdity, meaninglessness, moral silence, and social inaction of the modern hell (Camus, The Fall). In the ninth circle of hell is the frozen lake of "Cocytus" where Judas, Brutus, and Cassius can't speak because they are being chewed in the three mouths of the winged Lucifer for being traitors. In modern times the Enlightenment provides the stairway to the river Acheron and Cocytus because there is a Silence of Reason -- a lack of concepts and ideas by traitors to humanity for being silent in the face of overwhelming brutality and violence, class inequality, economic insecurity, anxiety, and human misery, on the one hand, and the poverty of our ideas, hopes, and the academy, on the other. The fragmentation of ideas and disciplines in the corporate liberal arts has produced a disenlightenment and eclipse of reason. Critically reacting to this, continental sociology, as an academic discipline incorporating social philosophy, political economy, and history, searched for the voice of concrete ethics and social justice. It represented a rejection of the distorting shadows of the Enlightenment with its narrow view of technical science and formal reason and the resulting degradation of moral and social ecology to the nothingness, loneliness, and despair of liberalism and capitalism. Imagination and creativity, reason and thought, and democracy and the environment all die in the darkness and shadows of the "hard times" of the Enlightenment.

**********************************

FOREIGN LANGUAGE TRANSLATIONS

Chinese Translation

of

Marx and the Ancients:

Classical Ethics, Social Justice, and

Nineteenth-Century Political Economy

Ma ke si yu gu ren:

Gu dian lun li xue, She hui zheng yi he

19 shi ji zheng zhi jing ji xue

(2011)

Japanese Translation

of

Classical Horizons:

The Origins of Sociology

in Ancient Greece

Kodai girishia to shakaigaku:

marukusu veba dyurukemu

(2017)

Chinese Translation

of

Marx and Aristotle:

Nineteenth-Century German Social Theory

and Classical Antiquity

Ma ke si yu ya li shi duo de:

Shi jiu shi ji de guo she hui li lun yu gu dian de gu dai

(2015)

EDUCATION

1964-1968

Manhattan College

4513 Manhattan College Parkway

Riverdale, New York 10471

B.A. in Philosophy, honors

June 1968

1968-1972

Boston College

Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts 02467

M.A. in Philosophy, August 1969

Ph.D. in Philosophy, June 1972

Dissertation Topic:

The Social Anthropology of Hegel and Marx

Summer 1972

U. S. Department of Justice

United States District Court

Southern District of New York

Foley Square, Manhattan, NY 10007

Indictment, Arrest Warrant, and Federal Trial

for Moral Resistance to Vietnam War and Draft Refusal

Felony Indictment: Failure to Report for Armed Services Induction

Summer 1973

Goethe Institute in Language Study

Blaubeuren, Baden-Württemberg, near Ulm

(2 months)

and

Brannenburg-Degerndorf, Bavaria, near Munich

(2 months)

West Germany

Deutscher Akademischer Austauschdienst

German Academic Exchange Service

Four-Month Language Fellowship (DAAD)

1973-1975

Johann Wolfgang Goethe Universität

Universität Frankfurt am Main

Institut für Sozialforschung

(The Frankfurt School of Critical Theory)

Bockenheim, Frankfurt am Main, West Germany

Deutscher Akademischer Austauschdienst

German Academic Exchange Service

Two-Year Research Fellowship (DAAD)

in Philosophy and Sociology

1971-1973 and 1975-1979

Graduate Faculty of Political and Social Science

The New School for Social Research

"University in Exile"

66 West 12th Street

New York, New York 10011

M.A. in Sociology, June 1973

Ph.D. in Sociology, June 1979

Dissertation Topic:

Systems Theory and the Engineering of Utopia:

Urban Technology and Planning in the Post-Industrial City

PUBLICATIONS:

BOOKS

Marx' Critique of Science and Positivism:

The Methodological Foundations of Political Economy

"Sovietica Series," vol. 53

Institute of East-European Studies

University of Fribourg, Switzerland

edited by T. J. Blakeley, Guido Küng, and Nikolaus Lobkowicz

(Dordrecht, Netherlands; Boston, Massachusetts; and

London, England: Kluwer Academic Publications, 1988)

Marx' Critique of Science and Positivism:

The Methodological Foundations of Political Economy

"Sovietica Series," vol. 53

edited by T. J. Blakeley, Guido Küng, and Nikolaus Lobkowicz

new publisher and reprint paperback edition

(Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer Publishing, 2012)

Marx and the Ancients:

Classical Ethics, Social Justice, and Nineteenth-Century Political Economy

(Savage, Maryland; London, England: Rowman &

Littlefield Publishers, 1990)

Marx and the Ancients

Chinese translation

Ma ke si yu gu ren:

Gu dian lun li xue, She hui zheng yi he 19 shi ji zheng zhi jing ji xue

translated by Wennan Wang

"Western Tradition: Classics and Interpretation -

Marx and the Western Tradition Series"

edited by Liu Forest

paperback edition

(Shanghai, China: East China Normal University Press, 2011)

Eclipse of Justice:

Ethics, Economics, and the Lost Traditions of American Catholicism

with Royal W. Rhodes

hardcover edition

(Maryknoll, New York: Orbis Books, 1992)

Eclipse of Justice:

Ethics, Economics, and the Lost Traditions of American Catholicism

with Royal W. Rhodes

new publisher & reprint paperback edition

(Eugene, Oregon: Wipf and Stock Publishers, 2009)

Marx and Aristotle:

Nineteenth-Century German Social Theory and Classical Antiquity

collection of essays

edited by George E. McCarthy

"Perspectives on Classical Political and Social Thought Series"

(Savage, Maryland; London, England: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 1992)

Marx and Aristotle

Chinese translation

Ma ke si yu ya li shi duo de:

Shi jiu shi ji de guo she hui li lun yu gu dian de gu dai

translated by Hao Yichun, Deng Xianzhen, and Wen Guiquan

"Western Tradition: Classics and Interpretation -

Marx and the Western Tradition Series"

edited by Liu Senlin

commentary by Chen Kaihua

paperback edition

(Shanghai, China: East China Normal University Press, 2015)

Dialectics and Decadence:

Echoes of Antiquity in Marx and Nietzsche

(Lanham, Maryland; London, England: Rowman &

Littlefield Publishers, 1994)

Romancing Antiquity:

German Critique of the Enlightenment from Weber to Habermas

(Lanham, Maryland; Oxford, England: Rowman &

Littlefield Publishers, 1997)

Objectivity and the Silence of Reason:

Weber, Habermas, and the Methodological Disputes in German Sociology

(New Brunswick, New Jersey; London, England: Transaction

Publishers, 2001)

Classical Horizons:

The Origins of Sociology in Ancient Greece

Choice Outstanding Academic Title Award, January 2004

(Albany, New York: State University of New York Press,

2003)

Classical Horizons:

The Origins of Sociology in Ancient Greece

Recording for the Blind & Dyslexic

(Princeton, NJ: Audiobook on Compact Disk, 2003)

Classical Horizons:

The Origins of Sociology in Ancient Greece

Japanese translation

Kodai girishia to shakaigaku:

marukusu veba dyurukemu

(Japanese title)

Ancient Greece and Sociology:

Marx, Weber, and Durkheim

translated by Tatsuo Higuchi & Daisuke Tagami

paperback edition

(Tokyo, Japan: Shogakusya Publishers, 2017)

Dreams in Exile:

Rediscovering Science and Ethics in Nineteenth-Century Social Theory

(Albany, New York: State University of New York Press, 2009)

Marx and Social Justice:

Ethics and Natural Law in the Critique of Political Economy

"The Historical Materialism Book Series," vol. 147

hardcover edition

(Leiden, The Netherlands; Boston, Massachusetts:

Brill Publishers, 2018)

Marx and Social Justice:

Ethics and Natural Law in the Critique of Political Economy

"The Historical Materialism Book Series," vol. 147

new publisher & reprint paperback edition

Haymarket Books at the

Center for Economic Research and Social Change

(Chicago, Illinois: Haymarket Books, 2019)

Shadows of the Enlightenment:

The Hidden Politics and Ideology of the Natural and Social Sciences

(New York, New York: published by Monthly Review Press,

imprint by New York University Press, August 2025)

********************************

Justice Beyond Heaven:

Natural Law and Economic Democracy in

U.S., German, and Irish Catholic Social Thought

co-authored with Royal W. Rhodes

(Amherst, New York: Humanity Books,

forthcoming: the first three chapters on German

Catholic social thought have been completed)

Existentialism and Classical Social Theory:

The Foundations of Sociology in the European Crisis of Meaning

(future project)

COURSES AT KENYON COLLEGE

(LISTEN TO AUDIO LECTURES OF COURSES)

(Click on the blue course number in the left-hand column for more information about

the syllabus, course description, required readings, and digital audio recordings for each course)

Socy

102 |

Social Dreamers:

Marx, Nietzsche, and Freud

(Introductory Sociology Course)

|

| Socy

222 |

State and Political Economy:

Profits and Poverty in the

Welfare State |

| Socy

234 |

Communitarianism and Social

Democracy |

| Socy

242 |

Science, Society, and

the Environment:

Integrating Ecological and

Social Justice

(Environmental Studies Program)

|

| Socy

243 |

Social Justice:

The Ancient and Modern

Traditions

(Legal Studies Program)

|

| Socy

248 |

Modernity and the Ancients |

| Socy

324 |

Natural Law and Natural Rights

Theory |

| Socy

360 |

Kant, Hegel, and

Modern Social Theory |

| Socy 361 |

Classical Social Theory:

Marx, Weber, and Durkheim |

| Socy

362 |

Contemporary Social Theory |

| Socy

461 |

German Social Theory:

From Freud to Habermas |

| Socy

474 |

Western Marxism:

Critical Theory of the

Frankfurt School |

| National

Endowment for the Humanities Project |

Democracy and Social Justice:

Ancient and Modern |

****************************

MANY OF THE COURSES LISTED ABOVE ARE ON DIGITAL

AUDIO AND VIDEO HARD DRIVES IN THE ARCHIVES

OF CHALMERS LIBRARY AT KENYON COLLEGE

ACADEMIC AND INTELLECTUAL

BIOGRAPHY

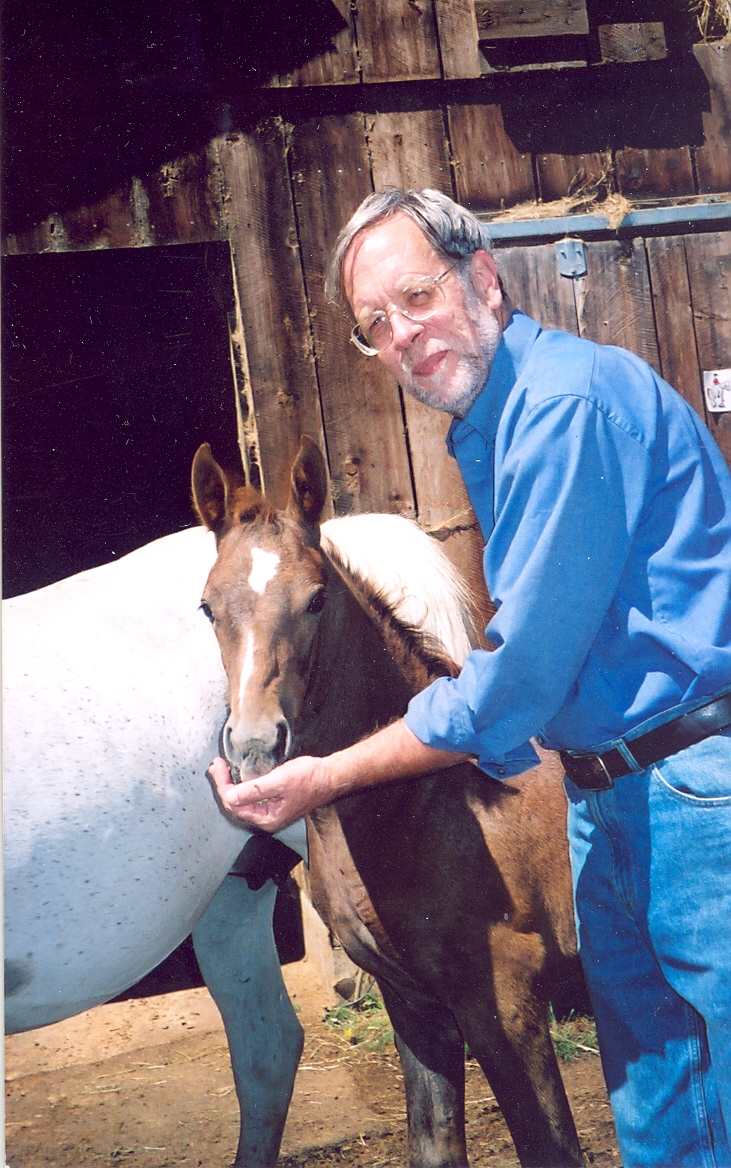

PROF. GEORGE E. MCCARTHY

NATIONAL ENDOWMENT FOR THE HUMANITIES

DISTINGUISHED TEACHING PROFESSOR

OF SOCIOLOGY

KENYON COLLEGE

Professor George E. McCarthy is an American and Irish philosopher/sociologist who teaches nineteenth- and twentieth-century European philosophy, classical and contemporary social theory, ethics and social justice, philosophy and sociology of science, and critical political economy at Kenyon College, Gambier, Ohio. He holds a B.A. in philosophy from Manhattan College (1968), an M.A. and Ph.D. in philosophy from Boston College (1972), and an M.A. and Ph.D. in sociology with a minor in political economy from the Graduate Faculty, New School for Social Research (1979). He studied progressive and Marxian economics at the New School with Professors David Gordon and Stephen Hymer. At an early stage in his academic career, there was a time (1971-1972) when he was enrolled simultaneously in two different universities, in two different graduate programs, in two different academic disciplines -- Philosophy and Sociology -- in two different cities, in two different states, while he was also under federal indictment, prosecution, and trial at the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York (SDNY) in Foley Square, Manhattan, NY, for military draft refusal, based on his moral resistance to the Vietnam War. And, in between these two American graduate school experiences, he spent four months at a Goethe Institute in Blaubeuren and Brannenburg-Degerndorf and two years studying the critical social and political theory of the Frankfurt School at the University of Frankfurt and the Institute for Social Research in Frankfurt/Main, Germany (1973-1975). In summary, it was during these 10 years after college between 1968 and 1979 that McCarthy attended graduate schools in philosophy and sociology in Boston and New York; received multiple graduate degrees; undertook scholarly research in Frankfurt, Germany; and was tried in a federal district court for refusal to serve in an immoral war of American imperialism and genocide.

These invaluable experiences provided the foundation for his later professional career with his integration of philosophy, sociology, and political economy and his synthesis of ancient and modern traditions. Classical Greece and the Athenian polity provided the inspiration and dreams for a better ethical and political life in continental social theory, while political economy and history provided the substance and structures for a more critical, concrete, and relevant theory of social justice. Philosophy without social theory and political economy is abstract, empty, and metaphysical -- without relevance and application to historical and social reality, while social theory and political economy without philosophy are meaningless and blind -- without political vision and ethical purpose

Earlier at Manhattan College in the mid-nineteen sixties he received an unusual classical education in the Great Books Curriculum of the Liberal Arts whose readings went from the primary texts of Greek and Roman antiquity to the modern Continental classics. During the four years of undergraduate training at Manhattan, all students enrolled at the college in the humanities and sciences were required to take four courses each semester in History, Philosophy, Literature, and Art in addition to two other classes usually in language and their academic major. During his first year of study, he took the four required courses focusing on Classical Greece and Rome. In these classes he read Plato and Aristotle; Herodotus and Thucydides; and Homer, Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripides, and Aristophanes. His first experiences and classes as a young undergraduate student were in reading about the philosophical discoveries and differences between Socrates and Plato, Aristotle's reflections in the Nicomachean Ethics and the Politics (Aristotle's lecture notes) on the ethics and politics of the good and virtuous life within the ideal and best forms of government; the Trojan War and exciting and romantic adventures of Odysseus throughout the Mediterranean as he returned home to the island of Ithaca; the Persian War and the battles of Thermopylae and Salamis; the Peloponnesian War between Sparta and Athens and Pericles's funeral oration about the need to protect and preserve Athenian democracy; the tragedies and comedies of classical Greece; and the exquisite and enrapturing beauty and grace of the Athenian Parthenon and Greek sculpture and art. Later in the second semester of his first year his attention turned to Roman philosophy, literature, history, and art. During the second year he repeated these same four subject areas for Medieval Europe. His third and fourth years continued this same approach and course listings with their emphasis on the primary texts for Modern and Contemporary European authors respectively. In addition to these four required courses each semester for four continuous years, he also took three years of German language and two years of additional Continental Philosophy classes in his major. This resulted in students at Manhattan College taking on average six courses per semester. The academic emphasis was clearly on Continental philosophy, history, and culture. At the time, there were very few social science courses offered at the college and they were usually connected with the business school since they were not considered part of the liberal arts tradition.

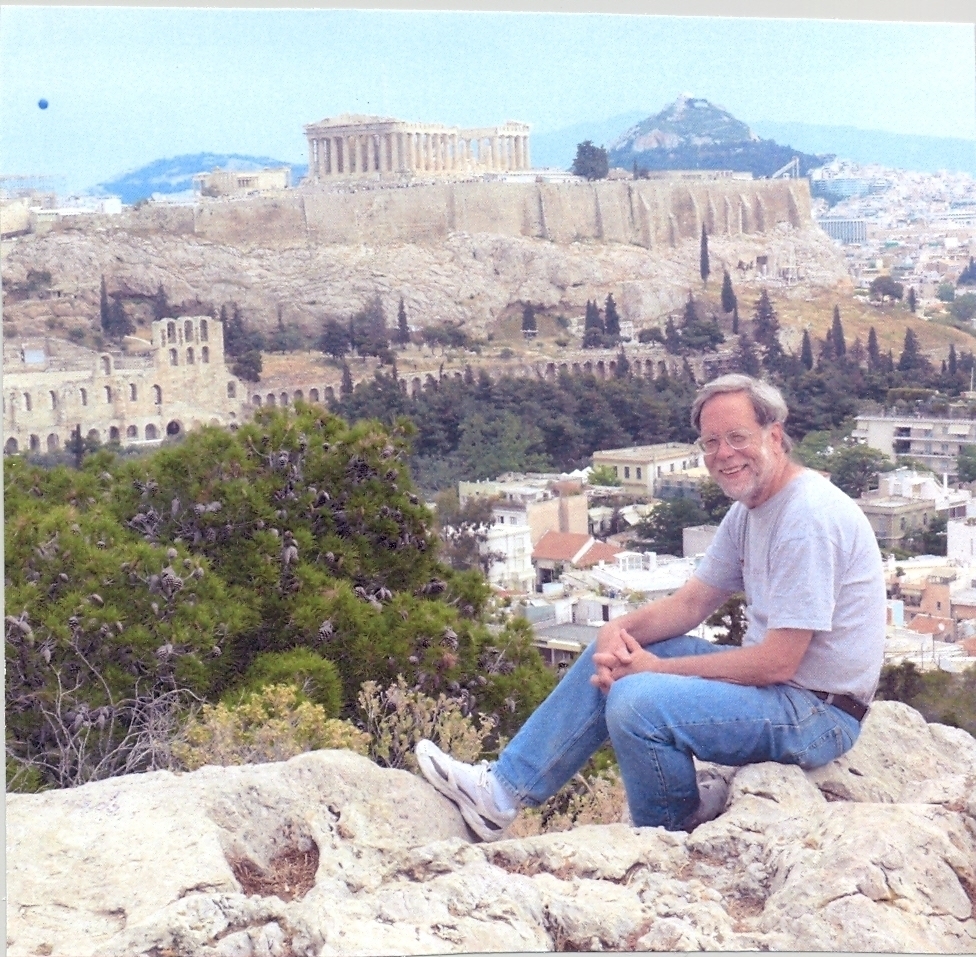

Having received an exciting and unforgettable classical education at Manhattan College in the sixties, his later scholarly inquires into modern sociology, political economy, and history were always grounded in the political vision, aesthetic creativity, and classical horizons of the democratic polity of ancient Athens from the Pnyx and the discursive Assembly to the heights of the Acropolis and the overwhelming beauty of the Parthenon, and from the funeral oration of Pericles during the Peloponnesian War with Sparta to the funeral oration of Marx after the execution of the last citizens of the Paris Commune at the Communards' Wall in the Pere Lachaise Cemetery. The classics help us overcome the disenchanted blindness and dark shadows of Enlightenment reason and capitalist society in order to hope and dream of alternative social possibilities for a better future and more humane and compassionate society. The ultimate goal of education is not to produce formal and technical utility, but to encourage students and faculty to imagine and dream -- to create Beauty in art, ethics, and politics.

After his formal education, McCarthy would then spend a good portion of his academic career searching the classical foundations and horizons of nineteenth- and twentieth-century European social theory and continental philosophy and raising the crucial question of why the modern authors of these theories would return to the Ancients for their creative inspiration, insight, and direction. Herein lies the true foundations of Classical and Contemporary European Social Theory. From this perspective, his main educational goal was to show how modern social theory reunited these lost humanistic traditions by rediscovering the ancient classics and integrating them with British political economy and anthropology, German and French social theory and philosophy, the German historical school of economics, and German, French, and British romantic poetry. For example, in the nineteenth century, Marx, after studying at the universities of Bonn and Berlin and writing a dissertation on the philosophy of nature of Democritus and Epicurus, combined the German romanticism of Schiller, Goethe, and Heine, the British romanticism of Wordsworth, Byron, Shelley, and Keats, the British classical economics of Smith, Malthus, and Ricardo, the idealism of Kant, Hegel, and Schelling, and the socialism of Rousseau, Fourier, Saint-Simon, and Proudhon with the beauty, creativity, and democracy of classical Greece to be able to imagine and dream about a better political and economic life beyond liberalism and capitalism in his comprehensive theory of social justice. And it is in this theory of social justice that he examined the nature of civil/legal, workplace, political, economic, distributive, and ecological justice based on the ideals and institutions of the following historical examples: (1) classical Athenian democracy; (2) the universal political rights of the citizen in the French Constitutions of 1791, 1793, and 1795; (3) the Paris Commune of 1871; and (4) the Iroquois Confederacy and the Great League of Peace. Today in the twenty-first century, it is the critical task of social theorists to expand and develop these ideals to reflect the historical and structural transformations of contemporary society in various countries. The ultimate goal of empirical and historical research is to examine the actual institutional changes in political economy that have been attempted in one way or another in European and Nordic countries to implement some form or elements of true democracy and socialism based on the above mentioned principles and ideals.

Academic Experience, Study, and Research in Germany: McCarthy has been a DAAD Research Fellow (Deutscher Akademischer Austauschdienst) at the Johann Wolfgang Goethe Universität (University of Frankfurt) and the Institut für Sozialforschung in Frankfurt am Main. He has also been a guest research professor at the Geschwister-Scholl-Institut für Politikwissenschaft at the Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, the Katholische Sozialwissenschaftliche Zentralstelle in Mönchengladbach, and the department of Philosophie und Erziehungswissenschaft-Humanwissenschaften at the Gesamthochschule, Universität Kassel, Germany. In 1994-1995, he was a Senior Fulbright Research Fellow in Germany at the University of Kassel. In the spring of 2000 he received the National Endowment for the Humanities Distinguished Teaching Professorship in Sociology at Kenyon College. More recently, he has been the recipient of a twelve-month National Endowment for the Humanities Research Fellowship (2006-2007) for his project, "Aristotle and Kant in Classical Social Theory," which examined the relationship between nineteenth-century European social theory and Greek and German philosophy.

His main educational goals are: (1) to investigate the philosophical foundations of nineteenth- and twentieth-century European social theory with a special focus on the integration of the Ancients (Ancient Hebrews, Hellenes, and Hellenists) and the Moderns (German Romantics, Idealists, Historians, and Critical Materialists); (2) to help rediscover the nature of sociology as an empirical/historical and practical/ethical science; (3) to reintegrate Philosophy, History, and Political Economy back into a Critical Social Theory; (4) to expand the nature of 'social science' beyond traditional quantitative and qualitative methods to include the full range of critical social science, including interpretive and hermeneutical science (Hermeneutische Wissenschaft or verstehende Soziologie), cultural science (Kulturwissenschaft), historical science (Geschichtswissenschaft or sociology of social institutions and structures), human or moral science (Geisteswissenschaft), historical materialism (political economy), dialectical or critical science (Kritische Wissenschaft: immanent critic of the values, logic, and dialectic of capital), and depth hermeneutics (Tiefenhermeneutik: neo-Freudian analysis of the unconscious mind), while rejecting the methodology of the natural sciences: positivism, empiricism, critical rationalism, naturalism, and nominalism; (5) to develop a critical social theory that incorporates classical and contemporary European social theory -- philosophy, history, and political economy -- into a comprehensive theory of social justice; (6) to integrate the vision and ideals of philosophy with the structures and historical reality of economic and social theory; (7) to expand quantitative and qualitative methods while liberating them from the narrowness of analytic philosophy and positivism (scientism and naturalism); and (8) to interpret Marx's labor theory of value, abstract labor, surplus value, and exchange value, as well as his theory of the structural contradictions (Widersprüche) and economic crises of capitalism in his later writings, not as part of a theory predicting the inevitable breakdown of the economic system, but as a critical theory of ethics and social justice. McCarthy has attempted to integrate these goals in his ten published books mainly in the area of 19th- and 20th-century German social theory, with another forthcoming, and three translated works in either Chinese or Japanese. For him, teaching and publishing are dialectically interrelated and interdependent since they reinforce, reinvigorate, and support each other. Scholarship and classroom presentations, book outlines and lecture notes, and the love for the ancients and the moderns are intimately bound together, since in the end, one teaches one's books.

The main goal of these eight points in education and scholarship is to revive the spirit of nineteenth- and twentieth-century European social theory and their classical horizons at a time when we are witnessing the decline and eclipse of reason in the American academy. Higher education has been turned into a technical and specialized education business and corporate structure with a corresponding split between the humanities and the social and natural sciences. The result has been a narrowing and shallowing of disciplines without theoretical imagination, creativity, and critical insight. Important ethical, historical, and theoretical questions are no longer capable of being considered due to the limited range of issues under discussion within the various disciplines themselves. Theory within sociology, along with epistemology, methodology, and metatheory, is being reduced to a peripheral and unnecessary afterthought of literature review, content analysis, research summary, and a perfunctory history of ideas. Theory is reduced to a quantitative and naturalistic analysis of theoretical texts, themes, and ideas that abandon critical hermeneutics, intellectual history, and philosophical traditions. In the process, theory is reified into a scientific data base that loses all meaning and relevancy. Classical and contemporary social theory becomes irrelevant to the examination of society as a whole, since its sole purpose is to precipitate a scientific study of society; the connections between sociology and the humanities are lost, as well as the profound questions of Continental Social Theory.

More specifically, Marx's goal was to draw the connections between Ancient philosophy and the Greek polis and Modern social theory and political economy in order to reconfigure and reinterpret Aristotle's major works Nicomachean Ethics (Philosophy: human excellence, happiness (eudaimonia), and the good life of moral and intellectual virtue (arete) from courage, moderation, and wisdom to friendship and citizenship) and The Politics (Sociology: institutions and structures of political economy, moral economy, and political democracy) for the modern age. This rewrite took the form of joining together Ethics, Social Theory, and Social Justice. The main academic goal behind this effort was to fuse the intellectual horizons (Horizontverschmelzung) of Philosophy and Sociology, Ethics and Social Theory, Virtue & Natural Law and Political & Economic Democracy, and Social Justice and Social Science, thereby creating a critical and dialectical discipline or Science with Heart (Herz: ethics, virtue, and moral/social principles) and Spirit (Geist: social ethics, political community, social institutions, and justice). With their help this approach created a hermeneutical method of interpretation of classical and modern texts by which great ancient and modern writings in social theory, politics, economics, and ethics were read and interpreted within and through the traditions that gave them birth and identity. With their help and the fusion of the ancient and modern theorists, it became possible to dream of a future democratic, egalitarian, and just society within a moral economy. It became possible to creatively dream with critical insight and practical vision while also looking back to the Ancients for inspiration, compassion, and hope (Griechensehnsucht). These ideas can best be expressed in a summary of McCarthy's academic interests and writings in the following areas of research: (1) Aristotle's theory of the Athenian democratic polity as the primary and best constitution in Classical Greece; (2) the connections between Marx's early writings on philosophy and his later works on democracy and political economy as reflecting the connection between Aristotle's Ethics and Politics); (3) Marx's ideal political economy in the form of social justice; and (4) Marx's debt to Moses and the Prophets of the Old Testament, Apostles and Followers of the Way in the New Testament, philosophers of classical Greece, and medieval Schoolmen for his critical understanding of communalism, democracy, and social justice.

Technically, unlike Aristotle, Marx did not write an initial or early work devoted entirely to ethics, but his early writings joined Ancient Ethics and Modern Political Economy in his focus on the centrality of human excellence, virtue (moral and dignified life and social justice), practical human activity, and creative moral and political action/work (Praxis). Marx took the ideals of a virtuous life -- the values, principles, and actions that help citizens realize their potential as true rational human beings -- and the essential happiness of moral existence from Aristotle and combined it with the world of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century "Creative Subjectivity" found in epistemology, moral philosophy, art, and economics. That is, he borrowed from the Romantic poetry of art, beauty, and creativity and the Kantian and Hegelian idealism of the constitution theory of truth (transcendental and phenomenological subjectivity) and morality (categorical imperative and social ethics). To these central themes he added the importance of modern economics and the virtue and value of human labor, industrial and agricultural production, political rights and democratic polity, and economic cooperatives of equality, freedom, and collective sharing of material wealth (French socialism). To Aristotle's ethics, politics, and defense of the Athenian democratic polity as the best constitution in Classical Greece, Marx added the crucial importance of the social, practical, and moral value & virtue of human labor in modern industrial society. Human physical, mental, and spiritual labor helped to provide the moral, political, and material foundations for human excellence, happiness, and the good life. And where Aristotle began his Nicomachean Ethics with the moral virtues of love, compassion, and friendship among family, friends, and citizens to establish the foundations and integrity of the Athenian polis and democracy, Marx focused instead in his Early Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts of 1844 on the nineteenth-century values and virtues of artisans, co-workers, and co-creators and their collective moral responsibilities of economic cooperation and mutual sharing within both the workplace and the polity. In the end, however, they both completed their works with the ethical dreams of Ancient and Modern democracy and the possibilities for the historical realization of humanity's essence as moral and social beings -- the realization of virtue, excellence, and happiness in political economy.

The following three essays below are only more concise and expanded outlines and summaries of previous writings. They were written mainly during the Covid pandemic (2020-2022): (1) summary of Aristotle's Ethics and Politics and their influence on Marx's humanistic ethic, political economy, and theory of social justice; (2) a chapter-by-chapter outline of the classical traditions -- Ancient Hebrews (Old Testament), Hellenes (Greek philosophy), Hellenists (New Testament), and Hegelians (German Idealism) -- and their incorporation into Marx's social theory; and (3) critical analysis of the epistemology, methodology, metaphysics, and politics of the natural and social sciences and the resulting eclipse and loss of social theory in American positivism (empiricism and rationalism) and sociology (quantitative and qualitative methods). The third essay is part of a larger work and assumes the critique of natural science in phenomenology, existentialism, post-analytic philosophy, American pragmatism, Marxian sociology, and critical theory as it examines the negative and destructive impact of positivism and its scientific model on social science and sociology in particular. The result is a specialization and fragmentation of naturalistic disciplines, reduction of social theory to a narrow scientistic methodology and metatheory, a nominalist loss of substantive and ethical reason, and the inability to develop a holistic and comprehensive theory of modern industrial and neo-liberal society. The result of this evolution of contemporary "scientific sociology" represents a loss of empirical and historical research, a loss of holistic and critical social theory, a loss of the historical and philosophical traditions grounding social theory, and a loss of an evaluative theory of social justice. In positivism, method creates objectivity and truth in both its empirical facts and predictive validation, its scientific experiments and social reality. Positivist science does not reflect reality, but rather, constructs a certain form of reality that makes critical social theory impossible, as well as any serious attempt at intelligently talking about an emancipated society based on the principles of social justice. The result of this approach and reductionist understanding of "science" ends in a "silencing, liquidation, and eclipse of reason" in the academy. In the U.S. academy and the social sciences, Method creates Social Theory, while in the European tradition, esp. German and French social science, it is the theory that creates the various methods of research and science. This explains why social theory in the U.S. disappears as an integrative, holistic, structural, and critical element in contemporary sociology to be replaced by hypothesis construction, scientific experiments, and research summaries. This is the "eclipse and liquidation of reason." Social theory is replaced by a mechanical and formalistic history of ideas as the disenchantment and separation between the humanities and social sciences only widens and the possibility for reflective and critical social change only lessens. Theory is stripped of its classical horizons and traditions; is eclipsed of all substantive and objective reason; and disappears in the form of social amnesia from the American academy. Theory simply becomes an ad hoc addition, an afterthought, an ahistorical and asocial content analysis, or a simple a summary of positivist research and science. But the grand theories of classical and contemporary Continental thought are gone in the grand academic eclipse. All this occurs because of the "objectivity" and demagoguery of formal reason.

Horizons at the End Reflecting on the Beginning: To dream of the future and change it, it is first necessary to creatively remember the classical horizons of the past. Now at the end, the beginning must be recalled and a memory of those who helped start the process of revisiting the classical and critical horizons must be remembered and recognized -- thanks to the early philosophical insights and theoretical scholarship of Erich Fromm, Bertell Ollman, Shlomo Avineri, Herbert Marcuse, and Max Horkheimer and the creative imagination and teaching commitments of William McCormick, Alfred Di Lascia, William Moran, Thomas Blakeley, and Trent Schroyer. Finally, mention should be made of Royal Rhodes with whom McCarthy had team-taught the course Social Justice: The Ancient and Modern Traditions for 36 years ending in the Fall of 2017 (see course outline and syllabus above). Rhodes, who holds an M.A. from Yale Divinity School and a PhD in the history of religion from Harvard University, provided the imaginative and creative inspiration and poetic vision for the course.

**************************************************

*************************************

Aristotle and Marx on Social Justice:

Ethics and the Natural Law of Freedom, Creativity,

and Self-Determination in the Critique of Political Economy

Analytical Marxism and The Tucker-Wood Thesis: There have been a number of social and political theorists within the Analytical Marxist and Anglo-American traditions between 1970 and 1990 who have argued that Marx did not have an ethical or moral philosophy or a theory of social justice, at least comparable to John Rawls and Robert Nozick. There are three distinct groups of thought within this broad theoretical and philosophical tradition that evolved over time. They argued that (1) Marx clearly did not have a theory of justice because of his critical theory of liberalism, labor theory of value, wage labor, historical materialism, and his epistemology and theory of science -- concepts of justice and morality are "outdated verbal trivia" and pure ideology (Tucker and Wood); (2) although he did not have a theory of justice, he did have an ethical philosophy based on clearly articulated moral principles of freedom, equality, fairness, alienation, and economic distribution; and (3) contrary to 1 and 2, Marx did have a limited theory of justice but it was based on a liberal understanding of civil law, individual rights, and distributive justice. This famous thesis, that Marx rejected social justice and moral thought, was originally developed in the writings of Robert Tucker and Allen Wood and continued by D. Allen, A. Collier, A. Buchanan, and A. Skillen. Some of the main arguments in the broader analytical tradition critical of any theory of social justice in Marx are as follows:

(1) There is no need for the liberal ideals of justice in socialism since justice is an ideological concept of the capitalist economy and, thus, Marx did not use the term of "justice" in his writings

(2) Justice is simply a juridical category and civic principle applicable only within liberalism and capitalism and refers mainly to issues of the state's legal system, that is, civil and legal rights for the protection of individual possessions, property, and liberty. This approach represents an ahistorical, deterministic, and mechanical interpretation of Marx's theory of historical materialism

(3) Marx's goal was to leave behind the old ideals of liberalism and, by rejecting natural rights and medieval natural law, he also was rejecting the use of the idea of justice -- in the process, they separated ethics and politics or civic morality from the moral economy and democratic polity

(4) Moral philosophy was viewed as limited and historical and therefore reflective of the principles of relativism and historicism as defined by a certain interpretation of historical materialism

(5) Liberal justice does not refer to issues of worker's self-determination, creative freedom, moral community, the laws of beauty, and human need

(6) The Analytical Marxists reduce justice, rights, and liberties to legal and civil rights of the natural rights tradition

(7) Justice is a form of religious or false consciousness, moral ideology, or useless moralizing that ultimately ends in justifying capitalism

(8) Following the path of neo-classical economics and rational choice theory, they thought that the market was ultimately fair and rational; wage labor was not exploitative or unjust; and that surplus value was necessary for further economic development and expansion (Ricardo) -- in the process they missed the ethical importance of the distinctions among labor, labor power, and surplus labor in Marx's theory of value by maintaining that profits came from the exchange process and not from production and labor exploitation of the social relations of production

(9) By rejecting justice, Marx was simply reduced by some Analytical Marxists to demanding fair wages and fair employment contracts in commodity production, and, thus, fair economic distribution -- others argued that, because of his criticisms of Proudhon and Lassalle, he also rejected the idea of distributive justice

(10) Marx in his later writings left behind his early and less mature philosophical writings of his post-graduate days and focused more on developing a positivistic and naturalistic science of economics -- scientific socialism -- with its prediction of economic crises and inevitable structural breakdown and collapse of capitalism in his voluminous work on Capital. This was his science of historical and dialectical materialism. They also maintained that science in the form of naturalism and nominalism is contradictory to ethics and moral critique, thus separating ethics from science, morality from political economy, Moralität from Sittlichkeit, and his early from later writings

(11) they denuded Marx of his critical and dialectical theory of capital, his labor theory of value, secular and historical natural law, theory of work, human potentiality, creativity, and self-determination (epistemological and practical constructivism), and human need, historical materialism, theory of exploitation, alienation, and surplus value, and his theory of economic and communal democracy

(12) the Analytical Marxists replaced German Idealism (which they saw as a speculative, superficial, and a false metaphysics), German and British Romanticism, French Socialism, and Classical Economics with neoclassical economics and critical rationalism (Popper). Some even rejected Hegel's dialectic and returned to Rawls and Nozick for insight; according to the methodology of historical materialism, others rejected morals and ethics as pure ideology since they were an historical and social production of modern society. They reduced Marxism to a form of neoliberalism, positivism, and the belief that justice only represents fair wages and payment for labor power and proper distribution -- they, too, reduce justice to abstract moralizing

(13) They thought Marx's ideal was "beyond justice," since in a socialist society there would be no need for justice. Analytical Marxism is Marxism without Marx and without his return to the classical traditions as the former reduced justice to simple legal categories, rights, and liberties, as well as a narrow interpretations of economic distribution based on market exchange and rational self-interest. In the end, justice is not necessary for a social critique, since it was ultimately a moral ideology justifying capitalism and liberalism. They failed to see that Marx integrated the Ancients and the Moderns into a comprehensive critical theory of social justice. The Analytical Marxists fused the method of modern science with neo-classical economics eliminating any need for discussing issues of social justice. The latter group thought Marx was "beyond justice." The Analytical Marxists began to redefined the areas of Ethics, Economics, Politics, Science, and Justice in new ways.

(14) There is another group within this Marxist tradition that, although rejecting a theory of Justice in Marx, argued that he did have a moral philosophy grounded in the ethical principles of equality and freedom. These modern theorists incorporated and retranslated Marx to fit the contemporary ideas in epistemology, politics, science, and the academy. This failure or unwillingness to see that Marx had a broader and more comprehensive theory of social justice is also based on a number of false premises and misunderstandings of the nature of justice itself. The Analytical Marxists defined the concept of justice in the very narrow terms of liberalism, civil rights, and economic distribution thereby limiting its application only to liberal politics and economics. They interpreted the concept mainly through the writings of John Rawls (A Theory of Justice, 1971) and not those of Aristotle. They also saw justice as a form of false consciousness and political ideology that ran counter to modern rationality and science, neo-classical economics, critical rationalism, and the principles of socialism itself. In order to fully appreciate Marx's theory of social justice one must first view his ideas in the context of his appreciation and integration of the history of Western thought and the classical traditions.

(15) Summary: The early Analytical Marxists and Neo-Positivists of the 1980s (Elster, Roemer, Cohen, Olin Wright, and Przeworski) rejected much of Marxian economics including his labor theory of value as the basis for surplus production, surplus value, and economic exploitation, his classical humanism, ethics, and theory of social justice, and his reliance on Hegel's logic and dialectic. Hegel's idealism, logic, and method were rejected as forms of speculative metaphysics and theoretical obscurantism. Marx, in turn, was criticized for not emphasizing the social world of empirical facts, causal laws, and scientific verification and truths, but making the distinctions between (1) the empirical appearances and underlying social reality; (2) the empirical world of market exchange and capitalist production and the hidden reality of worker alienation and exploitation; (3) the empirical world and its claims to individual rights, political freedoms, and market fairness and the hidden realm of false consciousness and political ideology; (4) historical and economic crises and the logical contradictions of capitalist production; and between (5) the laws of a market and industrial economy and the non-empirical ethical principles of classical humanism and social justice. Issues of alienation, exploitation, false consciousness, ideology, and the structural contradictions of capital, along with the moral principles of species being and social justice, are not scientifically and empirically measurable or testable aspects of society; the methods of critical continental sociology in general are not reducible to positivist methodology and research techniques. Nor are they capable of experimentation or reduction to universal and explanatory laws, nor reducible to intentional and individualistic decisions. They are humanistic borrowings from the Ancient Greeks, Modern Socialists, and German Idealists, and could thus be classified, and then ignored, as Marx's "early immature and philosophical writings" as opposed to his later more developed economic works.

(16) Exploitation Occurs within the Market and not Production: The Analytical Marxists replaced the classical and modern traditions of social justice by the logic of natural science, analytic philosophy, methodological individualism, rational choice theory and game theory, neoclassical economics, and a crude materialism of technological and economic determinism. Marx's theories of exploitation and alienation are removed from the arena of industrial production and placed in the market, that is, removed from the social relations of production and the labor theory of value, and placed in an analysis of unfair market exchange and individualistic intentionality. Finally, some of these themes within Analytical Marxism were rejected, adjusted, and modified by later members of this school of thought.

Summary of the Tucker-Wood Thesis: Iron Cage of Liberalism and Positivism: Marx from his early to his later writings did not have a theory of ethics or social justice because of the following scientific, epistemological, methodological, and historical reasons:

(a) Scientism and Naturalism: belief that Marx's methodology as an empirical scientific researcher made it impossible for him to undertake a moral or ethical critique of capitalism

(b) Nominalism and Relativism: the epistemological separation of facts from values, empirical research from ethical judgements also made an ethical critique of the industrial and class system of wage slavery impossible

(c) Positivism and Economism: interpreted Marx's view of science as focusing on the explanations, causes, and predictions of the structural contradictions, economic crises, and inevitable historical breakdown of capitalism

(d) Materialism and Historicism: argued that ideas, concepts, and theories are historically grounded and thus the direct product of a particular political economy and society that gave birth to them and cannot be used beyond that concrete historical moment as the basis for future social criticisms or the foundations for future social institutions

(e) Liberalism and Capitalism: argued that issues of legal rights, liberties, and justice in civil society and the state were exclusively products of modern liberal society and are not applicable to a future form of workers' control and democratic socialism.

The problem with the interpretation found in the Tucker-Wood Thesis outlined above is that it imprisoned Marx in various theories and traditions of science, knowledge, and history that he did not rely upon. As opposed to the Analytical Marxists, the Classical Marx was grounded not in positivism and analytic philosophy, but in the Aristotelian tradition of classical Greece. That is, his views of science and history were based in different intellectual traditions, both Ancient and Modern, that emphasized historical science, immanent critique, ethics, secular and historical natural law (practical humanism in art, literature, poetry, and philosophy, not religion or metaphysics), and dialectical science. In their analysis of Marx, Tucker and Wood emphasized modern positivism and not German idealism and constructivism; deterministic and mechanical materialism and not historical materialism; and Comtean and analytic philosophy of science and not the philosophy of Aristotle, Kant, and Hegel. They were caught in the logic of Liberalism and Positivism and, thus, were unable to imagine the emancipatory possibilities of social justice that lay within Marx's own critical social theory.

Marx concluded his famous work Capital not with an analysis of the historical and economic inevitability of the breakdown of capitalism as is generally believed, but with the recognition of the structural, logical, and ethical contradictions (Widersprüche) of the capitalist system that cannot be negated or overcome. His writings ended where they began in the mid-1840s with an emphasis on Aristotle and Hegel and an ethical critique of the moral and political failures of modern society -- the economic system is alienating and exploitative, irrational and immoral. (Note: Marx is aware in Capital that capitalism is a resilient economic system capable of transcending and negating these logical contradictions in history. Marx does not appear to develop an actual economic crisis theory that explains particular historical crisis, but rather, he develops a general theory of the overproduction of capital and the tendential fall in the rate of profit that explains the structural irrationality and immorality of this particular class system. See Paul Mattick, Marx and Keynes: The Limits of a Mixed Economy. pp. 60-82.) In the final analysis, the analytical tradition of Marxist thought in the 1970s mistook his rejection of isolated and ahistorical moral philosophy and their separation of Ethics and Politics for a critique of social justice. They eliminated any theory of justice in Marx by misreading and misinterpreting his critique of ideology and moralism and his theories of science, dialectics of ideals and economic structures, the logic of history, historical materialism, and political economy. Finally, and perhaps their most serious error, was to forget the Ancient and Modern traditions upon which Marx developed his theory of modern industrial society. And in so doing, they lost the soul (Ancient Hebrews and Early Christians), the heart (Ancient Greeks), and the spirit (Modern French and Germans) of his social theory, ideals, and vision -- they lost his ability to imagine and dream. As an alternative to this analytical perspective, Professor McCarthy recently published a book outlining Marx's six-point theory of social justice (see below in Part I: Ethics and Part II: Politics), while integrating the latter's early and later writings into an ethical and political whole. But first review the introductory summary of Marx's theory of social justice listed below.

*************************************************************************

Ethics, Politics, and Social Justice in Aristotle and Marx: Marx's theory of social justice was not limited to civil law or issues of worker's wages, fairness, or economic redistribution. It was much broader, comprehensive, and more profound than that. It delved into the question of the emancipation and self-realization of the historical essence of humanity in ethics, culture, law, politics, production, work, and its species being as a 'political and productive animal.' It focused on issues of happiness, moral and intellectual virtue, friendship, moral economy, political and economic democracy, human and natural rights, self-realization and self-determination of species being in political economy, individual freedom, dignity, beauty, and human creativity in material, cultural, spiritual, and political work, and economic distribution based on reciprocity and the satisfaction of fundamental human needs. Marx's true goal was the realization of the ethical values and political ideals of classical humanism in modern society in order to create a moral economy and self-government "of the people, by the people" for the common good. At one point in his addresses on the Paris Commune, he attempted to integrate the classical ideals Aristotle and Lincoln. The goal of justice was to affirm the existential meaning, purpose, beauty, and dignity of human life in its various social forms; it was to elevate humanity to a higher level of existence and value than a commodity of production, exchange, and consumption. Following the development in Aristotle's thought between the Nicomachean Ethics and The Politics, Marx, too, emphasized in his theory of justice the distinctions among morality, ethics, and virtue, social institutions and social structures, and social ethics. He incorporated Aristotle's Nicomachean Ethics and Politics (Aristotle's lecture notes) into his general social theory by expanding the nature of virtue, goodness, and happiness into a critical theory of political economy and the nature of a moral economy, physical, intellectual and moral labor, and economic democracy. Marx was very influenced by the philosophy of Classical Greece from his early German translation of Aristotle's De Anima (1840) and his doctoral dissertation in 1841 entitled Difference Between the Democritean and Epicurean Philosophy of Nature to his later parallel integration of Aristotle's ethics and politics in Capital (see Scott Meikle, Essentialism in the Thought of Karl Marx, 1985 where Aristotle is connected to Marx's Capital).

Ethics is an area of study that reflects the highest moral values, principles, and ideals of the good and virtuous life, while Politics examines the social institutions of political economy which nurture, protect, and ensure that existence of that moral life of humanity; these very institutions make virtue, happiness, and communal existence possible. The overall Structure, Logic, and Substance of Marx's theory of justice mirrors very closely that of Aristotle's theory: the latter begins with the classical humanism of ethics, moral virtue, happiness, and friendship in his Ethics and then evolves into a concrete historical and institutional examination of the Athenian polity and assembly, household and moral economy, and critique of unnatural wealth acquisition in a commercial market economy in his Politics. Marx, in turn, begins in his early philosophical writings with his examination of the political rights of the citizen and ethical humanism of species being and aesthetic human labor and then develops into a study of political and economic democracy, moral economy, and a critique of the irrationality and immorality of unnatural capitalist production, consumption, and market exchange in his later writings on Capital. Although Marx, for all practical purposes, does not have or use the terms "justice" or "social justice" in his writings, the overall Formal, Logical, and Substantive Structure of both authors' works and evolution of their theories are very similar and parallel each other closely.

As shown below, Marx borrows from Aristotle's Ethics and Politics the overall structure, logic, and much of the classical content of his critical analysis of capitalism from his early to his later writings, including his theory of participatory democracy, moral economy, forms of social justice, the ethical and humanistic foundation of society in human virtue, moral community, individual freedom, and personal dignity, and his critique of class property, privilege, and economic capitalism (class trade). This is then supplemented by his borrowings from the more modern traditions of French, German, and British idealism, romanticism, and socialism in order to explain the historical and social structures and contradictions of modern industrial capitalism. The generally accepted interpretation of the differences between Marx's early and later writings is that they expressed his transition from university philosophy to practical economics, Kant and Hegel to Smith and Ricardo, and abstract theory to social science. However, a more accurate picture is that these differences reflect his translation and integration of Aristotle's model and the movement from early Ethics (classical humanism) to later Politics (actualization of ethics in the ideal and best political and economic institutions).

Summary of the Marx/Aristotle Thesis: Stated succinctly, the overall logic and structure of Marx's theory of democratic socialism and social justice reside in Aristotle's The Nicomachean Ethics and The Politics. Marx borrows the ethics and politics, the moral philosophy, classical humanism, and institutional sociology of the economy and state from Aristotle adjusted for modern political economy, history, art, and philosophy. That is, between Aristotle's ethics and politics, Marx inserts modern economics, philosophy, literature, art, and democracy:

(1) Classical Greek Ethics: values and ideals of classical humanism expressed as moral and intellectual virtue, wisdom, and the good life

(2) Moral Economy and Distributive Justice: critique of early market capitalism, self-interest, and class wealth and property. Rejection of unequal distribution of wealth, commercial trade (kapelike), and money making and wealth acquisition (chrematistike) as disruptive of the ethics and politics of a democracy

(3) Politics and the Athenian Constitution: Athenian constitution of citizenship and a democratic polity (ideal democracy), including the Council, Assembly and Jury Courts which is then expanded to include modern humanism and socialist ideals. According to Aristotle, democracy was necessary to produce virtue and wisdom, political participation and discourse, collective judgement and wisdom, social stability, honesty and moderation, equality, liberty, and relative equality of property ownership, the common good, satisfaction of human needs, and practical judgement and public deliberation (Politics, chapter 3). These ideals of virtue, freedom, equality, and public discourse cannot be attained within a monarchy, aristocracy, or commercial trade economy. By critically juxtaposing and comparing the Ethics and Politics of these different political and economic systems, Aristotle is able to show that political inequality within a monarchy or aristocracy or the property, wealth, and class divisions created by commercial capitalism undermine the very possibilities of a true democratic society and a moral economy of household management (Oikonomia). Their values and institutions are antithetical to each other; concentrated political power and economic wealth are indifferent to democratic principles and institutions.

(4) Commercial Trade Economy vs Moral Exchange Economy & Capitalist Trade vs Household Economy and Democratic Polity: A material and successful life of commerce and trade dedicated to making money and acquiring property is not a noble or virtuous life. Aristotle argues that property should not be communally owned (critique of Plato), but there should be "a friendly arrangement for its common use" for the friendship, common good, and betterment of the political community (chapter 7, 1329b36); "property should belong to the people" (1329a17). The wealth of the polity should be used to facilitate virtuous citizenship, participation, political discourse, practical wisdom (phronesis), and a good and happy life. All citizens must have access to property (Politics, Penguin Books edition, 1981, pp. 115, 183, 201, 327, 370, 375, 393, 415-416, and 419). This is necessary for a polity based on equality, freedom, moderation, human dignity, public discourse, and political participation. All citizens participating in the good and virtuous life must be "sufficiently supported by material resources to facilitate participation in the actions that virtue calls for" (1323b36). Aristotle's theory of the incompatibility of commercial trade (kapelike) and unnatural wealth acquisition (chrematistike) with the ideals of a moral economy (oikonomia) and a democratic polity (politeia) are later retranslated and incorporated into Marx's theory of social justice and the contradictions between capitalism and democracy, self-interest, private property, and a class system and a society based on human dignity, creativity, self-determination, and the satisfaction of human needs -- physical, ethical, and aesthetic. Both social theorists believed that the principles and institutions of commercial capitalism and a trade economy (Aristotle) and industrial capitalism based on capital and private property (Marx) could not provide the material and economic foundations for either a moral economy or a truly democratic society. Both social systems make their political and ethical ideals and ideologies inconsistent and incoherent; a society based upon the tyranny of class, property, and extensive inequality and wealth divisions, whether it be in a monarchy, aristocracy, or capitalist plutocracy cannot nurture a society who goals are communal equality, freedom, self-determination, and social justice. The former theorist uses the dialectic of the Socratic method to reject monarchy and aristocracy as the best forms of government as he uses them merely to introduce the democratic polity as his ideal. And the latter theorist relies upon Hegel's theory of contradictions ((Widersprüche)) to undermine the rationality, logic, and ethics of capitalism in his dialectical method. [It is interesting to note that both Hegel and Marx in very different ways drew upon the loss of Aristotle's political theory and moral philosophy of the Greek polity in Western thought (Geist), which, in turn, would later be incorporated into Weber's thesis of rationalization, disenchantment, and the loss of substantive reason in the Enlightenment, utilitarianism, and formal rationality. See the writings of G. McCarthy, Marx and the Ancients and R. Solomon, in the Spirit of Hegel.]

*******************************************

(5) Modern Ethics, Ideals, and Moral Humanism: the ethics and moral values of German idealism, French socialism, and German/British romanticism --

self-determination, creativity, equality, freedom, beauty, and needs of human work

(6) Modern Politics and The Best Constitution of Democracy: the historical structures of industrial human labor, the modern European social system, democratic liberalism, representative government, individual rights and liberties, workers' ownership and control, and democratic socialism based on the following historical examples:

(a) the French Revolution, Constitutions of 1791, 1793, and 1795, and the Economic Rights of Man in liberty, security,

equality, and property and the Political Rights of the Citizen of 1789 in free thought, speech, and assembly

(b) Classical Athenian polity of the 4th century B.C.

(c) the Paris Commune of 1871

(d) the Haudenosaunee or Iroquois Confederacy of Nations in upper New York State and southeastern Canada

formed in the 12th century or 16th century (depending on different scholars' interpretation of history) and

ended during the Revolutionary War in the 18th century is the oldest and longest historical example of a

participatory democracy

(7) Modern Political Economy: the nature of value in the form of use value, exchange value, and surplus value

and the accumulation of profits and property in classical British political economy as the foundation of the

ethical, economic, and structural contradictions of capitalism.

The totality of Marx's writings are thus part of a comprehensive theory of social justice reflecting Aristotle's influence that may be divided into the following more specific areas:

Summary of the Substantive, Structural, and Formal Correspondence between Aristotle :::: Marx: Between Aristotle's

Ethics and Politics :::: Marx's Early Philosophical/Ethical and Later Economic/Political Writings

The Foundations of the Ancient and Modern Theories of Social Justice

Part I: Humanistic Ethics, Moral Excellence, and Moral/Intellectual Virtues: Classical Virtues of happiness,

love, compassion, friendship, citizenship, Praxis, good moral life (moral/political activity), and

household or family economy (Oikonomia), intellectual virtues of philosophical wisdom (Episteme),

artistic or technical knowledge (Techne), and ethical and political wisdom (Phronesis) and the

moral virtues of courage, moderation, and justice :::: modern virtues of creativity, beauty,

human dignity, Praxis (ethical and aesthetic Work), human emancipation, economic and political democracy,

brotherhood of man, friendship, citizenship, equality, freedom, cooperative sharing based on human need,

self-determination of non-alienated human nature or species being (Gattungswesen), social justice,

and ethical humanism. For both Aristotle and Marx, these humanistic and ethical values express the highest

forms of human need, moral virtue and human

excellence, as well as the highest forms of individual freedom,

human rights, and self-realization of human potentiality.

Part II: Expanding the Relationship Between Ancient and Modern ETHICS and POLITICS: Marx builds

upon Aristotle's Ethics and Politics by adding another key dimension pertaining to human labor

in an industrial society whereby ETHICS--POLITICS becomes ETHICS--WORK--POLITICS.

In the process Marx integrates Ancient ethics, virtue, political wisdom, and the democratic polity with

the Modern emphasis on human labor, production, art, creativity, human dignity and communal sharing

and cooperation. Many of the characteristics of Ancient ethics and politics thereby become fused with and

expressions of human labor, especially the technical, moral, aesthetic, and political dimensions of labor.

With Marx, human labor becomes a central economic (artisanship and production), political (democracy),

aesthetic (art and beauty), and moral (dignity, creativity, and self-determination) category.

Between ETHICS and POLITICS lies the imagination and vision of a moral economy, socialism,

idealism, and romanticism.

Part III: Political and Economic Theory of the Best Constitutions: the Democratic Polity of Athens based on

direct democracy (demokratia), political equality (isonomia), public accountability (eisangelia), and

political wisdom (phronesis) :::: the Democratic Commune of Paris based on class equality, public

participation, worker self-determination, and the collective ownership of the means of production and the

political rights of the citizen found in the French Revolution and French Constitutions of 1791, 1793, and 1795

and the Critique of the Gotha Program. Both forms of ancient and modern democracy were built on

a Moral Economy.

Part IV: Prerequisites for a Moral Economy: Household or Family Economy (Oikonomia) and Distribution

based on Reciprocity, Love, Friendship, Need, and Grace :::: Socialist or Workers/Cooperative Economy

based on Fairness, Need, and the Democratic and Collective Ownership of Production as the

Foundations of Democracy. Rejection of class inequality, property, and market profits.

Part V: Critique of Unnatural Wealth Acquisition: Compare Ancient Commercial Trade (Kapelike) :::: Modern

Capitalist Production -- Compare the Structural Contradictions (Widersprüche) and Loss of Virtue and

Reason found in the Ancient Exchange Market and Money/Profit/Property Accumulation of Chrematistike

using the Socratic Method and Immanent Critique of Dialogue and Dialectic :::: the Logical and Structural

Contradictions of Capital using Hegelian Logic and the Dialectic of Capital that destroy the moral

economy, democratic polity, and the future possibilities of humanity as a community of virtuous and

rational human beings. For both Aristotle and Marx, unnatural wealth acquisition and property

accumulation of commercial trade and industrial capitalism undermine the moral foundations of society

and the possibility of human virtue, equality, freedom, and happiness, that is, a justice society.

Part VI: Forms of Social Justice: Ancient Universal or Political Justice (moral excellence, virtue, and happiness

through politics) and Particular Justice (Rectificatory, Reciprocal, and Distributive Justice) :::: "Political